Carlos Larrauri

Carlos Larrauri: Thriving in Law School

Carlos A. Larrauri, MSN, ARNP, enjoyed a happy childhood with a loving, middle-class family in Miami, Florida. His mother was a Cuban-American and his father immigrated to the United States from Cuba by way of Venezuela. From his earliest years, Carlos was a gifted guitarist and loved skateboarding. Excelling in academics in high school, he attended Miami Killian Senior High School and the School for Advanced Studies, where he took dual enrollment classes for college credit. In 2006, he graduated with summa cum laude honors and as a National Hispanic Scholar. However, looking back, he feels that his work at that time was not his best, and he could have done better.

Entering high school, Carlos felt as though a “switch” had suddenly turned on, and he experienced feelings of isolation and loneliness. He was drawn to musical groups like Nirvana and other grunge artists. In hindsight, he realizes that sometimes artistic or creative lifestyles come with their own risk factors, including more latitude with substance use or disrupted sleep patterns. Some of the musicians he identified with endorsed the artistic subculture of the “stoner” guitar player or skateboarder, and yet he remembers that the music provided him with a sense of identity and validation of feelings that he was unable to fully articulate.

Carlos was exposed to marijuana as a young teenager the summer before high school. He began experimenting with cannabis for the first time, unknowingly searching for a coping mechanism he could not find in normal relationships. At first, it was a weekly activity, but soon, it turned into a daily habit. Daily drug use only aggravated his feelings of isolation. He was unable to fully concentrate, continued to struggle to find his identity, and could not connect with a healthy peer group where students were not using drugs.

At age 18, Carlos remembers his thoughts were like a “broken radio switching between channels.” Carlos was going through the “prodrome” phase of schizophrenia (a phase in schizophrenia prior to the first psychotic episode) with behavior changes that would soon progress into a full-blown psychosis. However, like many families, he and his parents saw these behavioral changes as a normal expression of adolescence and were entirely unaware that he would soon spiral into full-blown schizophrenia.

Carlos did well enough in high school to be accepted early into The Ohio State University (Ohio State) College of Medicine for a joint bachelor’s/medical school program. If he maintained a GPA of 3.2 in the degree program, he would be guaranteed a place in medical school. Though Carlos had dreamed of becoming an English professor, his father was a physician, and Carlos made the decision to follow in his father’s footsteps.

But the subtle early signs of mental illness cast a shadow over his first year at Ohio State. Moving to Ohio presented new challenges. As a Hispanic male, Carlos also began to feel like he was a member of a minority group, though he had never felt “different” growing up in Miami, surrounded by other Hispanic families. He was not prepared for the rigor and responsibility of college and felt isolated again. At that time, he became depressed, found it challenging to get out of bed, and he gained 30 pounds.

In hindsight, he believes he needed to see a counselor, but the stigma of mental illness prevented him from seeking help. When his GPA fell to 1.8 in his second semester at Ohio State, Carlos made the decision to call his mom, ask for help, and move back home.

Back in Florida, Carlos benefitted from a support network including family and many close friends. He soon felt he was back on track. He reflects, “Just like it takes a village to raise a child, that same village is necessary to heal a child’s mind.”

In 2008, Carlos enrolled at Miami Dade College and completed his associate degree. Shortly after the completion of his associate degree, he won a scholarship to attend the New College of Florida in Sarasota to pursue a bachelor’s degree in humanities.

However, while studying for his bachelor’s degree, his mental health problems came back to haunt him. He struggled with concentration and memory. He stared at his computer screen, was unable to complete assignments, and was skipping class. He was getting into cars with strangers, obsessed with the party culture, and heavily using drugs.

During his senior year at the New College of Florida, he began laughing and talking to himself, and running or playing basketball for hours at a time, often into the early hours of the morning. While trying to manage his excess energy, he was wholly unaware he was dealing with psychotic symptoms. He soon became preoccupied with religion and changed his academic focus from literature to religion. Carlos remembers this time as the onset of his first psychotic episode.

Entirely out of touch with regular life, he began looking for discarded food to eat on the university campus, picking up partially eaten hamburgers and other trashed food and smoking discarded cigarette butts. He also neglected his hygiene.

At times he realized that he was not well and that something was not right. Yet, he had become like a homeless person on campus.

During that semester, Carlos attended a life-changing meeting with his thesis advisor and his mom. Though his advisor confirmed that Carlos had a right to privacy, Carlos recognized that his mother would always be committed to helping him find his life. Carlos’s mother would also soon play a significant role in his journey to wellness.

Carlos’s family also had a close friend working at Harvard who was a specialist in schizophrenia in adolescents and children. He recognized Carlos’s behavior as a psychosis associated with schizophrenia. This friend emphasized the difference between “access to care” and “access to quality care,” hoping to give Carlos the best chance at a return to normal life.

Back at home with his parents again, Carlos and his family assembled the “dream team,” including a group of six researchers, physicians, and mental health professionals from the University of Miami. Initially, he received an inaccurate diagnosis of avoidant personality disorder and schizoid personality disorder from other providers, which delayed receiving care. Nevertheless, in December of 2010, at age 22, Carlos was finally diagnosed with schizophrenia. He was prescribed an antipsychotic medication, which enabled him to focus again. He also completely stopped using drugs and would never use drugs from that point forward. This was 13 years ago.

To this day, Carlos is thankful for his “dream team” and the recovery model. He was also empowered to be a part of his health decisions and doctors affirmed that it was still possible for him to have a happy life, full of meaningful relationships and work.

Carlos would not describe his recovery as an “on and off switch,” but as a “dimmer.” His symptoms gradually lessened. After two months on his medication regimen, his thoughts were clearer and his mood had greatly improved. Carlos found that having a supportive community of family and friends, including membership with the National Alliance on Mental Illness, was key in his recovery. Exercise, diet, and stress reduction techniques were also very important.

At one point, Carlos’s doctor said “It’s up to you, Carlos. If you take your medication and work towards your recovery, maybe you can still go back to school and graduate.”

Carlos did not go back to the campus of the New College of Florida; however, he had already completed all of his classes and only needed to finish his thesis in order to graduate. His advisor arranged for him to be able to complete his thesis at home. Unfortunately, despite finishing his thesis and earning his BA, Carlos did not return to this college campus to collect his degree on stage or graduate with his peers.

After completing his degree, Carlos worked in the food industry, waiting tables and cooking hamburgers. He was also not fully well and would not feel fully recovered for several more months. Considering his future, he made the decision to take community college classes at night to continue his education.

The next year, in 2013, Carlos successfully landed a job with Florida Judge Steven Leifman as part of the 11º Judicial Criminal Mental Health Project, a project at the intersection of mental health and criminal justice. Judge Leifman is an internationally renowned professional working to establish south Florida jail diversion programs and crisis intervention teams, helping people in the criminal justice system transition into housing in the community. Carlos worked for Judge Leifman for nine months, helping disabled persons apply for disability benefits. He felt he had finally found his niche.

Working with the mentally ill in the community under Judge Leifman motivated Carlos to return to school, as he hoped to make a greater impact. He considered both law and nursing. Realizing that a nursing degree was much more accessible, only costing him a few thousand dollars, compared to hundreds of thousands for law school, he chose nursing.

Carlos started his associate of science in nursing (ASN) in 2014 at Miami Dade College. At the start of his bachelor of science in nursing (BSN) program, Carlos continued to learn about mental illness and criminal justice through working the night shift at a maximum security forensic hospital while studying nursing in 2015-2016. After six months, he would give up his position at the forensic hospital which he describes as a “pressure cooker,” with Florida’s forensic system being one of the worst in the country.

Following the completion of his bachelor’s degree in nursing in 2016, Carlos found himself fully recovered and doing his best work. He decided to attend the University of Miami for his master’s of science in nursing (MSN) degree, graduating in 2017. Upon the completion of his degree, he worked as an adjunct and lecturer at the University of Miami, teaching nursing to undergraduates. Teaching at the college level had always been one of his dreams.

The following year, in 2018, he completed his psychiatric nurse mental health practitioner certificate.

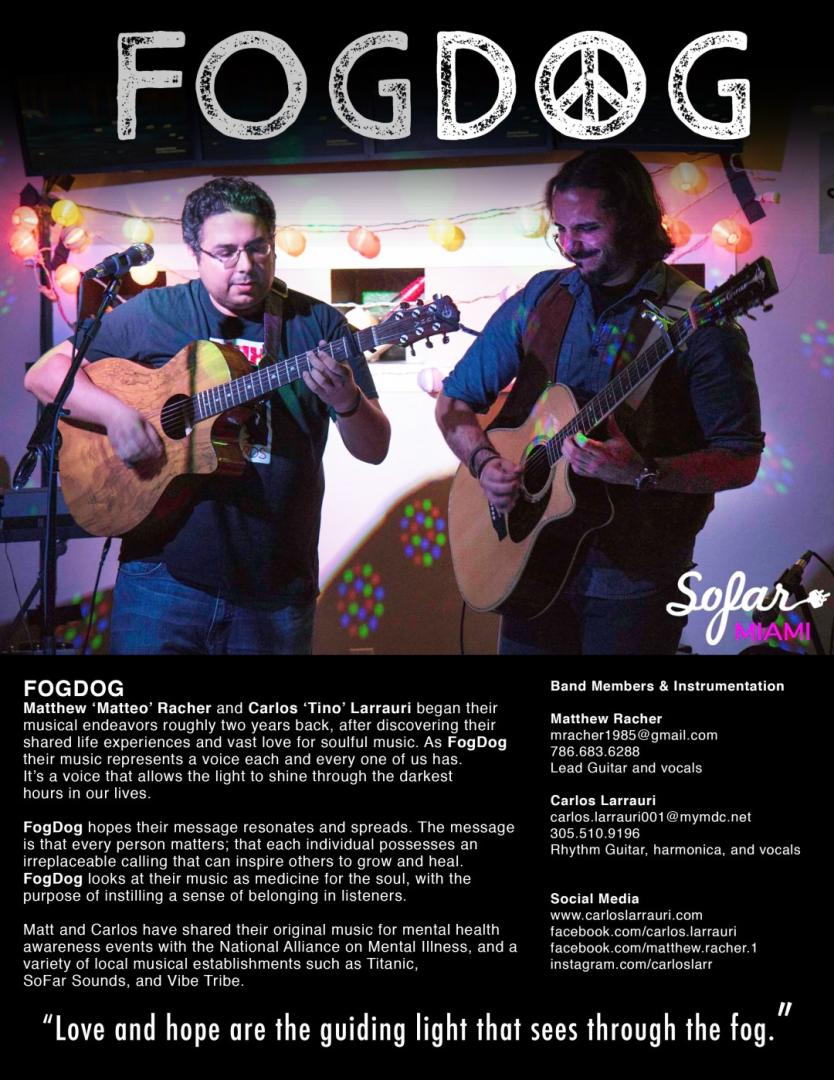

In his recovery, Carlos also collaborated with Matthew Racher, who was in recovery from mental illness as well, to create a band they called “FogDog.” To this day, Carlos is an active performer as a vocalist and guitarist with “FogDog.” Carlos and Matthew found they shared a vision for a band that “represents a voice inside of every individual struggling with their own mental health.”

In 2017, Carlos joined the Board of Directors of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) after serving several years with NAMI-Miami Dade County.

Carlos has enjoyed working full-time seeing patients. During his evenings in 2018-2020, he also studied for the LSAT law school aptitude exam, scoring in the 97 percentile. The University of Michigan reached out to Carlos, encouraging him to apply to their law school, and he was accepted to the University of Michigan in 2020 on a partial scholarship. Carlos was also accepted to the Kennedy School at Harvard University on a Zuckerman Fellowship to study for a concurrent master’s degree.

Today, while working to complete law school, Carlos studies and is also a part-time graduate student instructor at the University of Michigan. He is a member of the Global Scholars Program, looking at global social justice issues such as human rights, peace, nuclear proliferation, and environmentalism. These topics are discussed through a lens of cross-cultural dialogue within this diverse student cohort from different schools and STEM fields as well as the humanities. He recently gave a lecture on mental health and human rights.

As he looks ahead to graduating from law school, Carlos hopes to work in social justice, mental health advocacy, and human rights. He also hopes to someday find an academic role, working as a professor and is considering working in civil service as an elected or appointed official. This coming summer, he plans to work at a law firm in Washington, D.C.

Carlos never settled for less due to the diagnosis of schizophrenia and encourages others with the illness to dream big and never give up.

Today Carlos looks back on his struggle of dealing with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia in his formative years, at a time when young people decide where to go to college and start their career. Without early intervention, schizophrenia and related disorders can derail a young person. He feels the system of education in the United States lacks appreciation for what people with psychosis go through, and hopes that through sharing his story, there will be more compassion and accessible services to help struggling students achieve their best chance at success in school and at life.

On February 25 of 2023, Carlos married the love of his life, and began the next chapter of his journey.

Apresentando FogDog com Carlos “Tino” Larrauri e Matthew “Matteo” Racher.