梅根-考奇

Artist, Professor and Author: Meghan Caughey

View the condensed story in Newsletter Issue 24

I felt invincible when I was a little girl growing up in Atlanta, Georgia. My big brother would take me on hikes by the creek near our home. I played violin and cello and was a page in the Georgia State Legislature, where I lobbied for civil rights and against the war in Vietnam. I didn’t understand that my father had alcoholism or that anything was different in my family.

I assumed that I could do anything, but when I was 12 and my family moved to San Antonio, Texas, I was suddenly in what seemed like a strange and foreign land. In high school, I spent most of my time drawing and playing my cello, and I loved to spend time in nature. When I was 16, I discovered Zen Buddhism and explored meditation, and I spent most of my time alone.

When I selected a university, it wasn’t about the academic qualifications, but about how easily I could access the wilderness of the Rocky Mountains. I believed I needed solitude in the wilderness at the high altitude near the tree line. That was how I began college at Colorado State University. I studied art and spent as much time backpacking in the Rockies as possible.

Early in my first term, I had an experience I could never have predicted and will never forget. One afternoon in an art history class, I heard faint, intrusive, cruel voices that no one else could hear. When I struggled to return to my dormitory, the people I saw didn’t look normal— their faces looked like enormous insects. When I was finally in my dormitory room, and I looked at myself in the mirror, I was no longer human. I had turned into an awful beast. Although I tried my best to continue my studies and backpacking trips, my world was fearsome. Finally, one snowy night, some other students who saw how disturbed I was took me to the student health center. I was given the medication chlorpromazine (Thorazine) there, and I slept in a darkened room. Eventually, I was taken to see the psychiatrist. He sternly looked at me across his desk, and pointing his finger at me, he condemned, “You have schizophrenia.” Although I didn’t know what schizophrenia was, it was clear that I was doomed.

In the following years, I struggled to complete my studies and was often hospitalized for my symptoms, which were visual, kinesthetic and auditory hallucinations. I returned to San Antonio, where my parents were, and enrolled at Trinity University. I switched my major from art to psychology because I needed to understand what was happening to my brain. At one point, I was deeply discouraged and contemplating suicide, and I was able to do an independent study course in suicidology. I got college credit to obsess about killing myself. The irony of this was inescapable. My doctor would give me antipsychotic medications, but I hated how the side effects made me feel, so I usually would stop taking it and then end up in the psychiatric hospital. I would have to stay in the hospital until I could be stabilized by retaking the medication again. I went in and out of various hospitals but eventually graduated with a bachelor’s degree in psychology.

I decided on becoming an art therapist to combine art and psychology, so I went to graduate school in Vermont. It didn’t take long for my psychotic symptoms to become severe, even though I was working as an art therapy intern at the Vermont State Hospital. There, I saw a patient who had full-blown tardive dyskinesia, a serious movement disorder caused by the same medication I was taking. The sight terrified me. I ended up in the psychiatric hospital and, for the first time, was tied down with four-point leather restraints on my ankles and wrists. I had no memory of how I ended up in restraints, but it would not be the last time. Being tied down for hours is a profound experience.

I was told I would have to leave school and be treated in a residential psychiatric program. I resisted this, but eventually, it became unavoidable. Because I detested psychiatric medication, I ended up in an unusual program in Oakland, California. It was called the Cathexis Institute, and they claimed they could cure schizophrenia without using medications. Instead, they believed that psychosis was caused by faulty parenting and the cure was in “reparenting patients.” They physically held adults in the therapists’ laps and gave grown adults baby bottles of warm milk. They even would put adult patients in baby diapers, and the adults would regress to infancy and be cared for, including having baths and diaper changes. There was also the practice of corporal punishment if a patient broke a rule. My mother was told she was “schizophrenogenic,” meaning she had created my illness, and the program blamed her for inadequately nursing me when I was less than three months old, and said she was what had caused my disorder.

I stayed in this program because I was very motivated to get well, and they didn’t make me take medication, but eventually, I ran away. I ended up living in a cabin in the coastal mountains south of the south San Francisco area, and I intensely focused on my art.

I went in and out of psychiatric hospitals. I detested the medications because they caused movement problems, shaking, blurry vision, swelling of my breasts, lactation, dry mouth, and excessive sleepiness. And I especially detested the inevitable weight gain—this all made it very hard to draw and paint which was my passion, and I felt ashamed of myself—I didn’t understand why I had these side effects.

Eventually, I was determined to go to art school, and I finally completed an MA in drawing and painting and then an MFA in pictorial art. I did this despite the frequent hospitalizations.

I met a young man and fell in love, and we got married and moved to Santa Cruz, California.

In the first year of our marriage, I made a significant suicide attempt—being married could not ease my emotional pain. We moved to Oregon and, after seven years, were divorced. This was followed by years of many hospitalizations and suicide attempts. I have been hospitalized well over one hundred times, sometimes in the Intensive Care Unit, after trying to kill myself.

When not in the hospital, I attended a day treatment program. One day in the waiting room, I found a medical newsletter that listed schizophrenia medications that were being researched, and one caught my attention. It said it didn’t cause weight gain like most other medications, and it was in Phase III trials. I immediately had the feeling that this medication was going to change my life. I was 48 years old, and no one thought I would ever get out of the wards of psychiatric hospitals. With many calls to the drug company that made the medication, I got into a Phase III clinical trial in Southern California. I faithfully made the 16-hour trip from home to the California hospital every month for two years. I lost over 70 pounds, and my psychotic symptoms disappeared. And, remarkably, I started to experience a new feeling—I felt pleasure, for the first time in many years.

I stopped going to the hospital. The drug company trained me in public speaking. They paid me to fly across the country and travel in limousines to give presentations at medical conferences and mental health advocacy events.

Eventually, I pursued a career in mental health advocacy and peer-delivered services, services in which persons who themselves have recovered from their personal mental health challenges get special training and are able to work as peer specialists helping other persons who are still struggling with their problems. The peer specialist can sometimes empathetically connect with others who are having a hard time and because of their own experience, the peer specialist knows viscerally how to help.

No one had ever thought I could work, but my career began at age 50, even though my psychiatrist said I “was too sick to work.” I designed and directed mental health programs in Oregon as well as nationally. I finally ended up in Portland, Oregon, as senior director of peer wellness services at a large health nonprofit.

Now I am also a clinical assistant professor at the Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Psychiatry. I train psychiatry and doctoral residents in the Public Psychiatry Training program and also work with a suicide prevention program. I also have a consulting business.

In 2021 I had Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) caused by the antipsychotic medication that had saved my life. Because I can no longer take it, I have occasionally had ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). I am a survivor.

I continue to make art, play the cello, and write. I write poetry and essays. My memoir, Mud Flower, Surviving Schizophrenia and Suicide Through Art (2021) has won 12 book awards. My work has been shown and published internationally. I’m currently working on Making Art from the Lap of the Universe. In 1998 I received a Buddhist lay ordination and was given the name, Jisho, which means compassion for all living beings. This describes the motivation and purpose of my work.

Last year, I trained a cohort of peer wellness specialists in Cape Town, South Africa, and this year they are calling me the “Mother of the Program” which pleases me immensely.

Is it possible to heal from schizophrenia? I honestly must say that sometimes things can still be challenging, but it is possible to do something that may seem impossible to the average person. One does not have to accept the label of “mental patient’ if one insists on imagination and perseverance. It may not always be easy, but it is worth claiming one’s freedom!

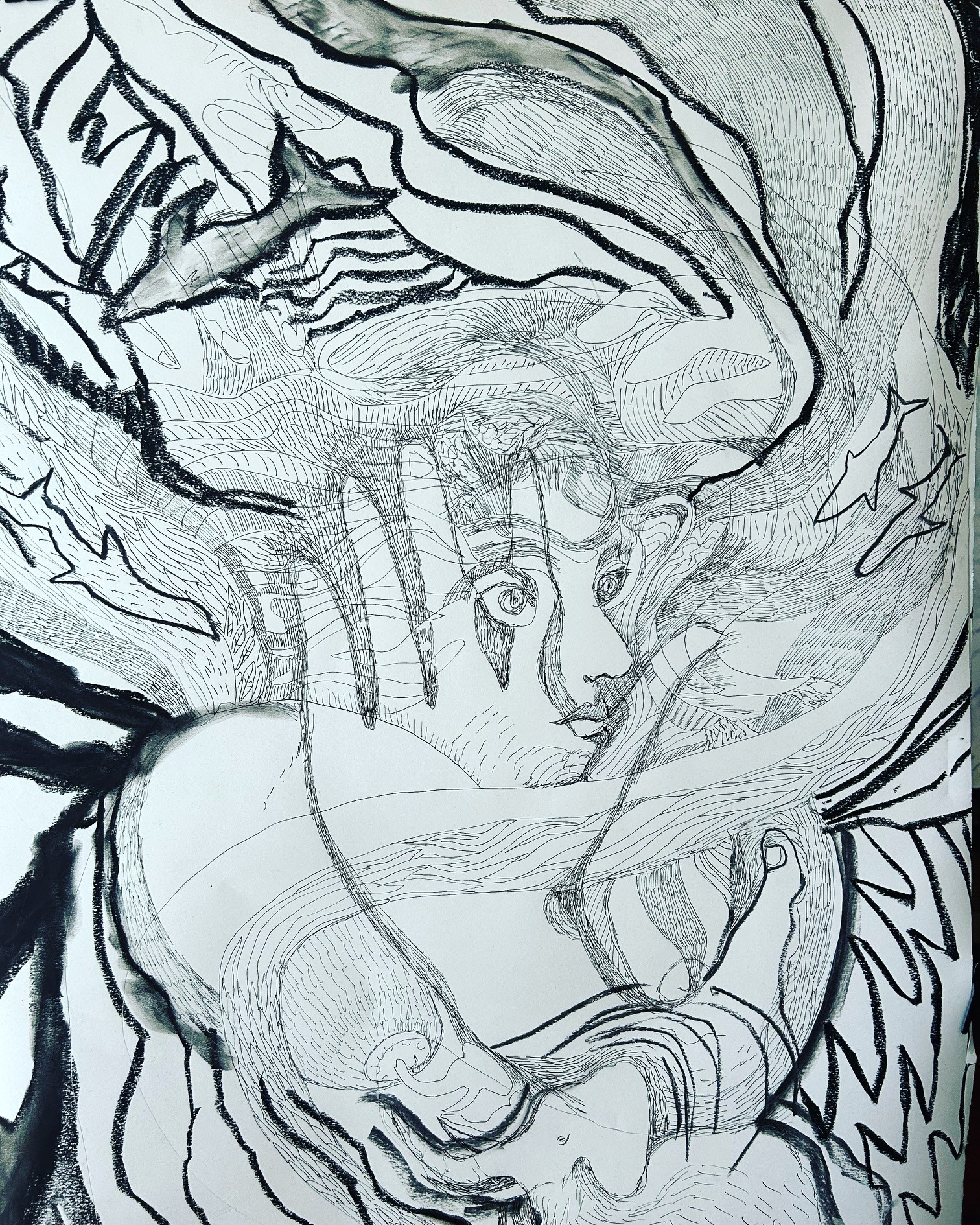

Winged Being Six

Meghan is currently working on a series of drawings for her new book in progress titled “Winged Beings: Marking Art from the Lap of the Universe.”

The drawings are pen and ink and charcoal on paper, 30″x 40.” I just invite the images to arise from my unconscious, and they basically draw themselves. I learned this way of “free drawing” when I was briefly in training to become an art therapist. The unconscious draws the picture.